Adverse selection is an important concept in the fields of economics as well as insurance and risk management. Sometimes known as “anti-selection,” Adverse selection describes circumstances in which either buyers or sellers use information that the other group does not have, specifically about risk factors related to a particular business undertaking/transaction. In these cases, when these two groups are informed to different degrees, this is known as asymmetric information. (The opposite of this situation is symmetric information, where both buyers and sellers have the same amount of knowledge.)

Naturally, the result is that one party has a consistent advantage over the other, which leads to inefficiency in the price of goods/services within the market. It leads to ill-informed, poor decisions on the part of either buyers or sellers.

More on Adverse Selection

In most cases, the party with a higher level of material knowledge is the seller, rather than the buyer. This is the case in markets including real estate, the stock market, used car sales (as well as sales of second-hand items in general, which may or may not be in good or reliable condition), and more. A big exception to this general rule is the insurance industry, where the buyer typically knows more than the seller. People who are more likely to take risks are also more likely to buy life insurance as well as disability insurance.

Adverse Selection in the Insurance Industry

The concept of adverse selection was first applied to the insurance industry, and since then it has been one of the most prominent areas where adverse selection occurs. This is because people with high-risk lifestyles (smokers, people employed in dangerous jobs, etc.) are more likely to seek out life and disability insurance, as they and their families are more likely to financially benefit from it. In these kinds of situations, the buyer has more knowledge than the seller—they know more about the risks they face to their health.

Insurance companies respond to this trend and reduce adverse selection by setting up significant limitations on coverage, or else by raising the cost of premiums quite high for high-risk policyholders.

Health insurance companies charge smokers more than non-smokers; car insurance companies charge new drivers (who are more likely to get into car accidents) significantly more than experienced drivers; and life insurance companies charge those in dangerous jobs (e.g. logging, commercial fishing) higher premiums. Insurance providers lower their risk of dealing with higher-cost claims through limited coverage as well as higher premiums.

Without these targeted price increases, adverse selection can instead lead to prices increasing overall. This is because companies will otherwise respond to the financial threat of adverse selection by raising prices across the board. This is done to account for losses from high-risk insurance policyholders. The result, though, is that lower-risk policyholders will choose not to invest in insurance.

Adverse Selection in the Marketplace

The adverse selection problem is by no means unique to the world of insurance. If sellers in any industry have more information than buyers, the latter is automatically disadvantaged, and are likely to be overcharged.

One example in the marketplace is that of used car sales. A car dealership might be aware that a car they are selling has a major flaw, one that is not immediately apparent to buyers. The dealership may fail to divulge this information and sell the car for more than it is worth; the buyer is effectively swindled.

Another marketplace-related example is selling shares of a company. The company’s management might be aware that they are selling shares for more than they are actually worth, and take advantage of this asymmetrical access to information. Without the same level of knowledge, buyers may purchase the overpriced shares.

Why Adverse Selection is a Problem

Adverse selection places a significant financial burden on insurance companies, for starters. This has negative effects for consumers, as well. The result is a smaller pool of insurance providers from which to select your insurance plan, as well as potentially much higher cost of insurance coverage.

Here is a more detailed explanation of why this outcome occurs: with fewer healthy, low-risk people being insured, the overall group of those who are insured contains considerably more high-risk policies. The ratio of total policies to claims paid out becomes lower and insurance companies cannot afford to continue providing insurance.

To compensate for these higher costs, insurance companies raise their rates. This leads to greater burdens on consumers and discourages even more people from purchasing insurance due to unaffordability (which perpetuates the problem even more).

Moral Hazard vs. Adverse Selection

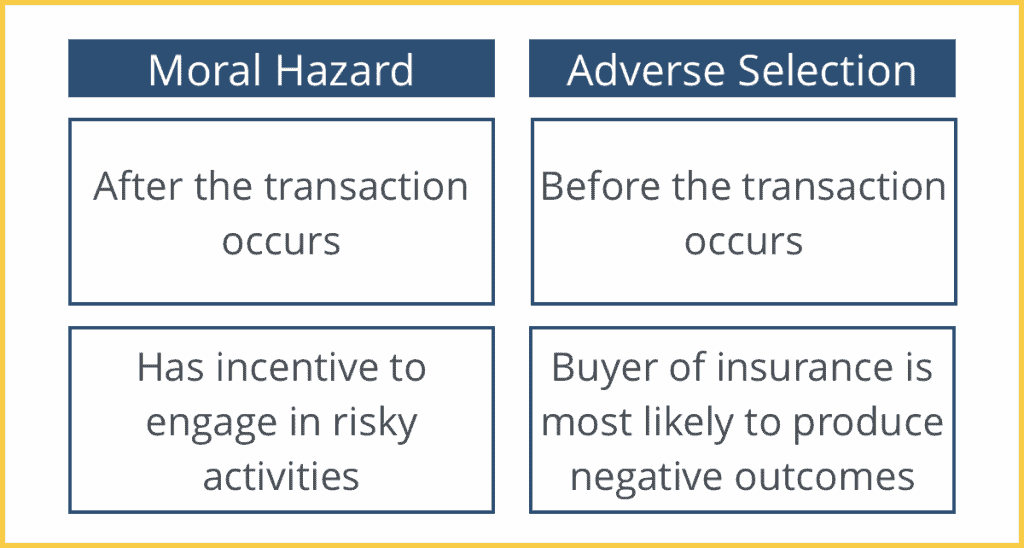

Adverse selection happens when one side of a deal has more information than the other—when there is a state of asymmetric information, as described above.

By contrast, moral hazard is when one side provides misleading information and, when protected from risk, is freed up to behave more recklessly than they would without this protection. People are incentivized to take risks in situations when other parties will be forced to take on the costs of those risks. For example, homeowners may be less careful once they have theft insurance, because they are financially covered in case of a robbery. This term is most commonly used in the insurance industry but is relevant to finance as well.

The two concepts are related—both involve asymmetric information. It is important to note that in practice, the most significant difference between the two terms is that adverse selection is focused on informational asymmetry before a deal goes through, while moral hazard is concerned with informational asymmetry following the deal.

Resolving Adverse Selection in the Health Insurance Industry

Adverse selection is a significant economic problem. It is also a medical problem when people do not have health insurance coverage or cannot afford the cost of their health insurance premiums. So, how to address it?

One strategy is for insurance companies to single out particular at-risk groups (e.g. those who smoke) and charge them extra health insurance premiums. However, this is frequently a discriminatory practice—smokers, for instance, tend to be lower-income people who cannot afford this extra financial burden. Other factors that can affect rates include age of the buyer and their location, based on postcode.

Another solution is the compulsory purchase of insurance: when individuals are required to purchase insurance. In the United States, private insurance means younger people with less need for medical care may avoid purchasing a health insurance plan. This is an example of adverse selection. The highly problematic result is that premiums in general end up being more expensive and those who need insurance have trouble paying for it.

In order to resolve this, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) used the mandatory purchase of insurance. Those who do not purchase insurance are financially penalized with an additional tax premium, which encourages those who might otherwise not take out insurance to do so. When people with fewer health issues—in other words, those who are a lower risk to insure—take out insurance, this makes insurance more affordable for everyone, particularly those vulnerable groups who really need it. However, the ACA’s strategies to address adverse selection in the health insurance market have not actually resolved the problem. More aggressive policy measures may be needed.